Landscape Photography in the Colonial Image Archive

Projections of Nature

von Silas Edwards

The Colonial Image Archive is most closely associated with the genre of colonial ethnographic photography, a technology used to categorise, police and dehumanise people living in the territories appropriated by the German empire. However, when I visited the archive in October as part of a field trip for a research seminar, the custodian Aisha Othman brought our attention to the presence of a second major genre of photography in the archive: landscape photography. Though these images might at first seem more benign—perhaps even appealing—they played an equally instrumental role in the German colonial project.

Entering the term ‘Landschaft’ into the search tool of the digital archive produces 1633 results of the same kind: wide, horizontal vistas showing landscapes ranging from savannahs and riverscapes to rocky mountain valleys, almost always devoid of people. A cursory rummage through the archive boxes and further searching in the digitised collection makes clear that photographs and lantern slides explicitly titled with the word ‘Landscape’ represent only a fraction of the total number of such images in the collection.

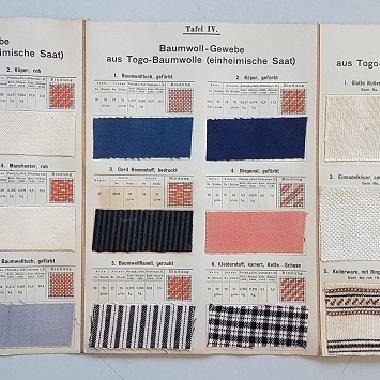

Colonial landscape photography served a variety of purposes. It could provide useful information about local terrain necessary for exercising military control, or inform debates in Germany about the crops, livestock or industries best suited to particular regions. Most important however—within the German Colonial Society’s campaigns to attract public support and investment for German colonial expansion—was the potential of landscape photography to fire up the imagination. And nowhere was this function more significant than in representations of Deutsch-Ostafrika (German East Africa, present-day Tansania, Burundi and Rwanda).

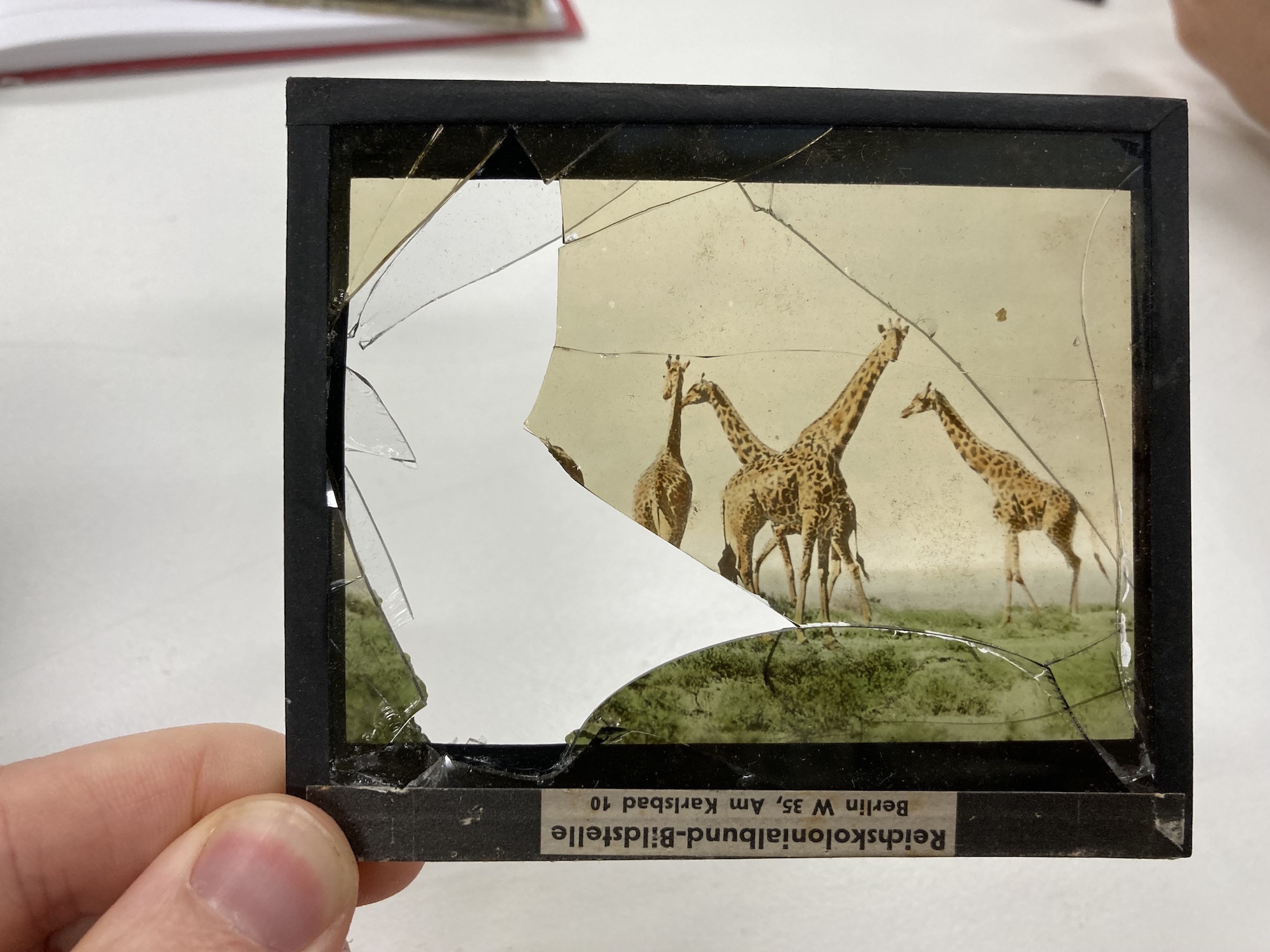

Images of landscapes in which local people such as the nomadic Massai were conveniently shuffled outside the view of the camera lens not only projected an idea of land and resources up for grabs (‘terra nullius’). They also fed a fantasy of wilderness: East Africa as an unchartered land of big game and unbridled nature. Anticipating the lantern slide shows of Carl Georg Schillings, the first celebrity hunter and wildlife photographer, the landscape photography in the colonial image archive bears witness to the birth of a conservation or ‘Naturschutz’ movement premised on hypocrisy. As Bernhard Gissibl documents in his book The Nature of German Imperialism, the period between 1885 and World War I witnessed the increasing use of wildlife conservation as a political and legal pretext to alienate and exclude indigenous people from the land on which they lived, a framework of preservation codified in the official founding of the Verein Naturschutzpark in 1909. While making the traditional hunting practices of indigenous people for clothing and food illegal and punishable by brutal penalties, the administration in Deutsch-Ostafrika increasingly profited from the promotion of hunting as a sport and form of entertainment for colonial officials and tourists, with stuffed animal parts sent back to Germany as trophies of white male conquest.

In this sense, the lantern slides produced for the German Colonial Society projected a certain vision of East African landscapes not only onto the walls of public lecture theatres in Germany, but also back onto those landscapes themselves, in the enforcement a colonial fantasy of wilderness which was achieved through the exclusion and persecution of local people. Moreover, as investigative journalism by the Taz newspaper has suggested, this framework of nature conservation persists in many ways unchanged today, with the expansion and policing of conservation zones funded by Western organisations often corresponding with the dispossession and eviction of people dwelling in Sub-Saharan Africa.

During the seminar The Enquiring Eye convened by Clémentine Deliss at the Städelschule in the summer semester of 2022, I partnered with the artist Rund Elalrabi to brainstorm possible approaches to exhibiting colonial landscape photography. While Tina Campt has theorised alternative methods of viewing ethnographic photography which pay notice to the defiant facial expressions of people subjected to the colonial gaze, we struggled to read the same possibility of a rebellious subject in photographs of landscapes. Instead, we were drawn to toying with the amorphous scale of landscape lantern slides, or to seeking out examples of smashed or faded images like the one shown here. Finally, we wondered how the globally interwoven processes of climate and biodiversity collapse might bind back together the future of East African and German landscapes. In what ways might it be possible to rethink the conventions of landscape photography, in a way that unsettles the colonial and patriarchal man/nature binary which continues to underlie many wildlife conservation projects?

Diese Objekterzählung wurde von Silas Edwards im Rahmen des Seminars “The Enquiring Eye” geschrieben, das von Clementine Deliss im Sommersemester 2022 veranstaltet wurde. Das Seminar untersuchte Debatten über die Zukunft umstrittener Sammlungen und nutzte die Sammlungen der Goethe-Universität als Rohmaterial für gemeinsame Forschungsprojekte zwischen Studentierenden der bildenden Kunst und Studierenden des Masterstudiengangs Curatorial Studies.

Literatur

Bernhard Gissibl (2019) The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa. Berghahn Books

Paul Munro (2021) “Colonial Wildlife Conservation and National Parks in Sub-Saharan Africa,”Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.195.

Sione Schlidwein (2020) “Das koloniale Erbe der Nationalpark”. Taz. Available at: https://taz.de/Militarisierter-Naturschutz-in-Afrika/!5671721/

Tina M. Campt (2017) Listening to Images. Duke University Press.